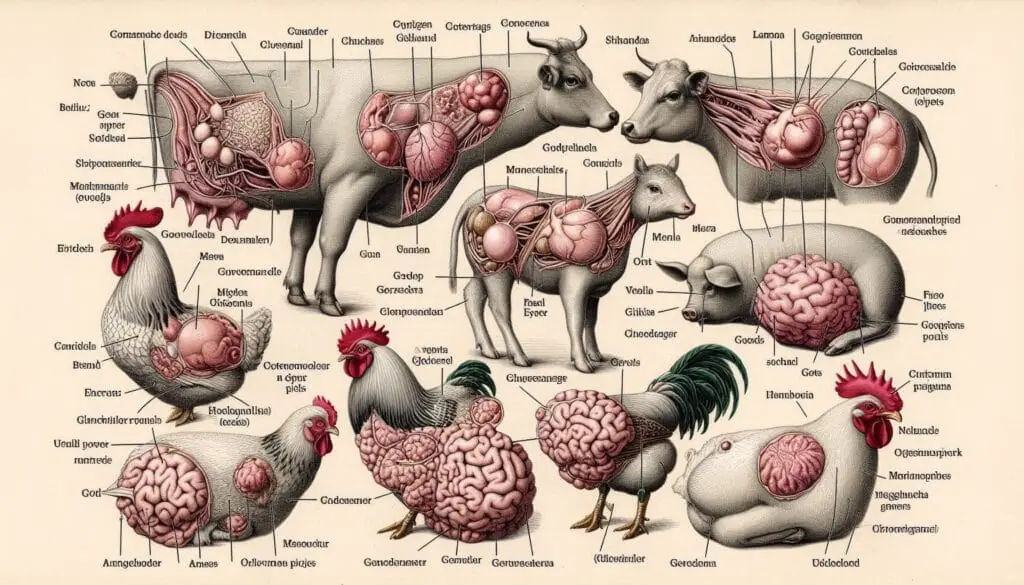

Non-Ruminant Digestive Organs

Introduction

The digestive system of non-ruminants, or monogastric animals, is uniquely structured to efficiently process food. Unlike ruminants, which have complex stomachs for fermenting fibrous materials, non-ruminants have a simpler digestive tract. This article will explore the various organs involved in digestion, their functions, and how they work together to ensure nutrient absorption.

Overview of Non-Ruminant Digestion

Non-ruminants include animals such as pigs, horses, and humans. Their digestive systems are designed for quick digestion and absorption of nutrients from energy-rich foods. Understanding these organs is crucial for animal husbandry and nutrition.

Key Digestive Organs

Mouth

The mouth is the entry point for food. Here, mechanical digestion begins as teeth break down food into smaller pieces. Saliva mixes with food to form a bolus, which is easier to swallow. Salivary enzymes start breaking down carbohydrates.

Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the mouth to the stomach. It uses peristalsis—wave-like muscle contractions—to push food down into the stomach.

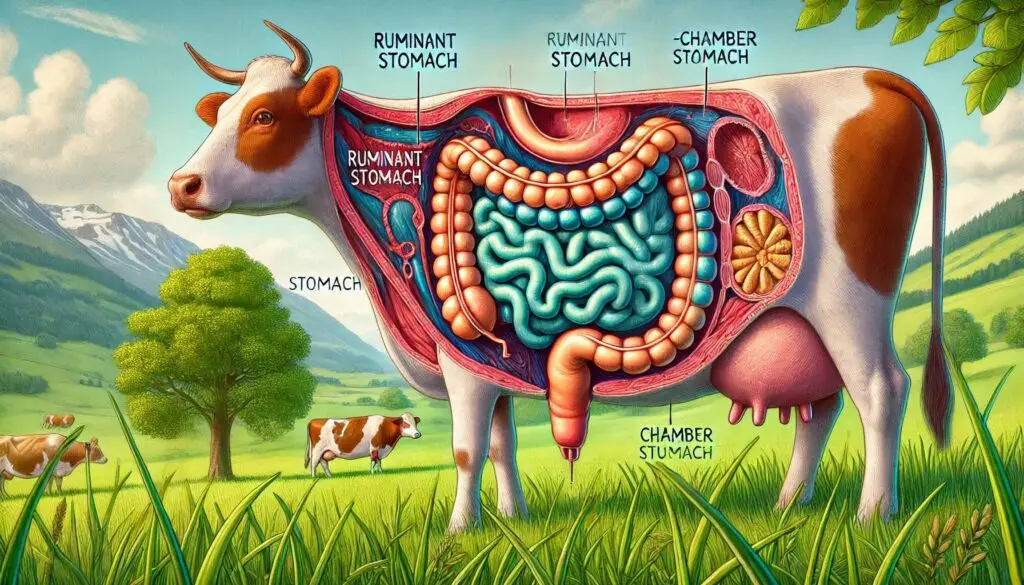

Stomach

In non-ruminants, the stomach is a single compartment where food is stored and mixed with gastric juices. These juices contain hydrochloric acid and enzymes that digest proteins. The acidic environment also helps kill harmful bacteria.

Small Intestine

The small intestine is where most digestion and absorption occur. It consists of three parts:

- Duodenum: The first section receives bile from the liver and pancreatic juices that aid in fat digestion.

- Jejunum: The middle section focuses on nutrient absorption.

- Ileum: The final section absorbs remaining nutrients before passing waste to the large intestine.

Large Intestine

The large intestine absorbs water and electrolytes from indigestible food matter. It consists of:

- Cecum: A small pouch that plays a minor role in digestion.

- Colon: Absorbs water and forms feces.

- Rectum: Stores feces until excretion.

Accessory Digestive Organs

Liver

The liver produces bile, essential for fat emulsification. Bile is stored in the gallbladder until needed. For more information on liver functions related to digestion, visit How Your Liver Works.

Pancreas

The pancreas secretes digestive enzymes into the small intestine. These enzymes break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. You can learn more about pancreatic functions at Pancreas Overview.

Digestive Processes in Non-Ruminants

Mechanical Digestion

Mechanical digestion begins in the mouth with chewing and continues in the stomach as food is mixed with gastric juices. This process breaks down food into smaller particles for easier enzymatic action.

Chemical Digestion

Chemical digestion involves enzymatic breakdown of macromolecules into absorbable units. For example:

- Carbohydrates are broken down into simple sugars.

- Proteins are digested into amino acids.

- Fats are emulsified by bile and broken down into fatty acids and glycerol.

Absorption

Most nutrient absorption occurs in the small intestine through villi—tiny finger-like projections that increase surface area. Nutrients pass through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream for distribution throughout the body.

Elimination

Indigestible materials move to the large intestine, where water is reabsorbed, and waste is compacted into feces before being expelled through the rectum.

Importance of Understanding Non-Ruminant Digestion

Understanding how non-ruminant digestive systems work can significantly impact animal health and nutrition management. Proper feeding strategies can enhance growth rates and overall health in livestock.

Feeding Strategies for Non-Ruminants

- Balanced Diets: Ensure diets are rich in energy but balanced with proteins, vitamins, and minerals.

- Digestibility: Use easily digestible feeds to maximize nutrient absorption.

- Regular Monitoring: Regularly assess animal health to adjust diets as needed.

Conclusion

The digestive system of non-ruminants is efficient at processing energy-rich foods quickly. By understanding each organ’s role—from the mouth to the rectum—farmers and pet owners can optimize diets for better health outcomes.

More from Veterinary Physiology:

https://wiseias.com/pancreas-in-animals/

https://wiseias.com/parathyroid-glands-in-animals/

https://wiseias.com/ovaries-in-animals/

Responses